Which Primary Layer Of The Skin Provides A Pink Undertone To Caucasian Skin?

Layers of the Skin

The Epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the pare, and protects the torso from the environment. The thickness of the epidermis varies in different types of skin; it is just .05 mm thick on the eyelids, and is 1.v mm thick on the palms and the soles of the feet. The epidermis contains the melanocytes (the cells in which melanoma develops), the Langerhans' cells (involved in the allowed system in the peel), Merkel cells and sensory nerves. The epidermis layer itself is made upwards of five sublayers that work together to continually rebuild the surface of the skin:

The Basal Prison cell Layer

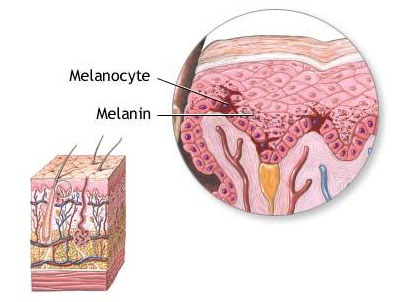

The basal layer is the innermost layer of the epidermis, and contains small-scale round cells called basal cells. The basal cells continually divide, and new cells constantly push older ones up toward the surface of the pare, where they are eventually shed. The basal cell layer is likewise known every bit the stratum germinativum due to the fact that it is constantly germinating (producing) new cells.

The basal cell layer contains cells called melanocytes. Melanocytes produce the skin coloring or paint known as melanin, which gives skin its tan or brown colour and helps protect the deeper layers of the skin from the harmful effects of the dominicus. Lord's day exposure causes melanocytes to increase production of melanin in order to protect the skin from damaging ultraviolet rays, producing a suntan. Patches of melanin in the skin cause birthmarks, freckles and historic period spots. Melanoma develops when melanocytes undergo malignant transformation.

Merkel cells, which are tactile cells of neuroectodermal origin, are also located in the basal layer of the epidermis.

The Squamous Prison cell Layer

The squamous prison cell layer is located above the basal layer, and is also known as the stratum spinosum or "spiny layer" due to the fact that the cells are held together with spiny projections. Inside this layer are the basal cells that have been pushed upward, nonetheless these maturing cells are now called squamous cells, or keratinocytes. Keratinocytes produce keratin, a tough, protective protein that makes up the majority of the structure of the skin, hair, and nails.

The squamous cell layer is the thickest layer of the epidermis, and is involved in the transfer of certain substances in and out of the torso. The squamous cell layer also contains cells called Langerhans cells. These cells attach themselves to antigens that invade damaged pare and alarm the immune system to their presence.

The Stratum Granulosum & the Stratum Lucidum

The keratinocytes from the squamous layer are then pushed upwards through ii thin epidermal layers called the stratum granulosum and the stratum lucidum. As these cells motility further towards the surface of the skin, they get bigger and flatter and attach together, and so somewhen get dehydrated and die. This process results in the cells fusing together into layers of tough, durable material, which continue to migrate up to the surface of the peel.

The Stratum Corneum

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis, and is fabricated upwards of ten to 30 thin layers of continually shedding, expressionless keratinocytes. The stratum corneum is also known equally the "horny layer," considering its cells are toughened similar an creature'due south horn. As the outermost cells age and habiliment downwards, they are replaced by new layers of strong, long-wearing cells. The stratum corneum is sloughed off continually as new cells have its place, only this shedding process slows downwardly with historic period. Complete cell turnover occurs every 28 to 30 days in immature adults, while the aforementioned process takes 45 to 50 days in elderly adults.

The Dermis

The dermis is located beneath the epidermis and is the thickest of the iii layers of the skin (1.5 to 4 mm thick), making up approximately 90 percent of the thickness of the peel. The main functions of the dermis are to regulate temperature and to supply the epidermis with nutrient-saturated blood. Much of the body's water supply is stored within the dermis. This layer contains most of the skins' specialized cells and structures, including:

- Blood Vessels

The blood vessels supply nutrients and oxygen to the peel and take away prison cell waste and cell products. The blood vessels too transport the vitamin D produced in the skin dorsum to the rest of the trunk. - Lymph Vessels

The lymph vessels breast-stroke the tissues of the skin with lymph, a milky substance that contains the infection-fighting cells of the allowed system. These cells work to destroy any infection or invading organisms as the lymph circulates to the lymph nodes. - Pilus Follicles

The hair follicle is a tube-shaped sheath that surrounds the part of the hair that is under the skin and nourishes the pilus. - Sweat Glands

The average person has about iii one thousand thousand sweat glands. Sweat glands are classified co-ordinate to 2 types:- Apocrine glands are specialized sweat glands that can exist institute merely in the armpits and pubic region. These glands secrete a milky sweat that encourages the growth of the bacteria responsible for body odor.

- Eccrine glands are the true sweat glands. Found over the unabridged trunk, these glands regulate trunk temperature by bringing water via the pores to the surface of the skin, where it evaporates and reduces peel temperature. These glands tin can produce upwardly to ii liters of sweat an hour, however, they secrete mostly water, which doesn't encourage the growth of odor-producing leaner.

- Sebaceous glands

Sebaceous, or oil, glands, are attached to hair follicles and can be establish everywhere on the trunk except for the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. These glands secrete oil that helps go on the skin smooth and supple. The oil also helps keep skin waterproof and protects against an overgrowth of bacteria and fungi on the skin. - Nervus Endings

The dermis layer also contains pain and touch receptors that transmit sensations of hurting, itch, force per unit area and information regarding temperature to the brain for interpretation. If necessary, shivering (involuntary contraction and relaxation of muscles) is triggered, generating body heat. - Collagen and Elastin

The dermis is held together by a protein chosen collagen, made by fibroblasts. Fibroblasts are skin cells that requite the skin its strength and resilience. Collagen is a tough, insoluble protein establish throughout the torso in the connective tissues that concur muscles and organs in identify. In the skin, collagen supports the epidermis, lending it its durability. Elastin, a like poly peptide, is the substance that allows the skin to jump back into place when stretched and keeps the pare flexible.

The dermis layer is made up of 2 sublayers:

The Papillary Layer

The upper, papillary layer, contains a sparse arrangement of collagen fibers. The papillary layer supplies nutrients to select layers of the epidermis and regulates temperature. Both of these functions are accomplished with a sparse, extensive vascular organisation that operates similarly to other vascular systems in the body. Constriction and expansion control the amount of blood that flows through the skin and dictate whether torso heat is dispelled when the peel is hot or conserved when it is cold.

The Reticular Layer

The lower, reticular layer, is thicker and fabricated of thick collagen fibers that are arranged in parallel to the surface of the skin. The reticular layer is denser than the papillary dermis, and information technology strengthens the pare, providing structure and elasticity. It also supports other components of the skin, such equally hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands.

The Subcutis

The subcutis is the innermost layer of the pare, and consists of a network of fat and collagen cells. The subcutis is also known as the hypodermis or subcutaneous layer, and functions equally both an insulator, conserving the body'southward heat, and as a shock-absorber, protecting the inner organs. It also stores fat as an energy reserve for the body. The claret vessels, nerves, lymph vessels, and hair follicles also cross through this layer. The thickness of the subcutis layer varies throughout the body and from person to person.

Source: https://training.seer.cancer.gov/melanoma/anatomy/layers.html

Posted by: buttswillart.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Primary Layer Of The Skin Provides A Pink Undertone To Caucasian Skin?"

Post a Comment